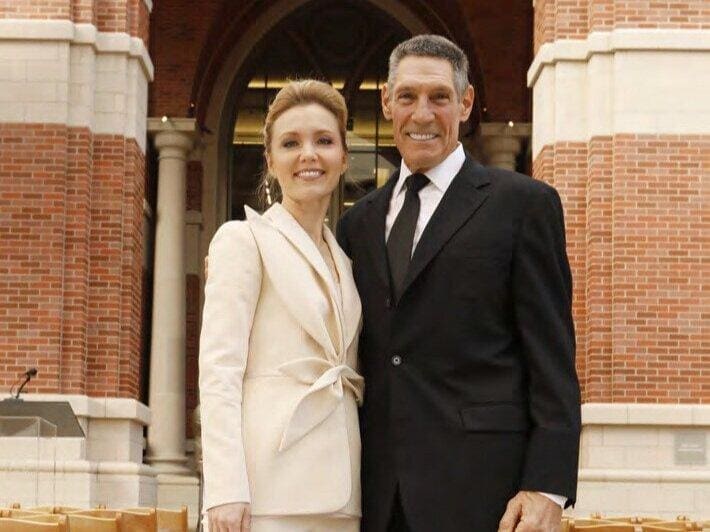

Dr. Gary K. Michelson and Alya Michelson are the heart of Michelson Philanthropies. Their passions have fueled the initiatives of the foundation, which marked its 25th anniversary in 2020. The couple discussed their future plans with Michelson Philanthropies Executive Director Geoffrey L. Baum.

In 2014, Dr. Gary K. Michelson and his wife, Alya, donated $50 million to the University of Southern California to create the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience, bringing together exceptional scientists, researchers, and engineers from around the world to work collaboratively on solutions to today’s most pressing health issues. Located at Michelson Hall (which was dedicated on November 1, 2017), this 190,000-square-foot interdisciplinary research facility is a model for other research universities, bringing the world closer to the medical breakthroughs that are redefining the 21st century.

Gary: I used to joke that it was David’s job to make the money so I could give it away, but it’s much more complicated than that. [David Cohen is CEO and chief investment officer of Karlin Asset Management, the private investment firm created by Dr. Michelson in 2005 after he reached a $1.35-billion patent acquisition settlement with Medtronic.] David conducts our business with the highest ethical standards. We have tried to do well while we’re doing good.

How do you see our foundation differently than other philanthropic models out there?

Gary: I can never give enough credit to Mike Milken. In 2005, when I reached the settlement with Medtronic, I had no idea how to be effectively philanthropic. People who know me have heard me say that life is not fair. And I have gotten way too much. At some point, you have to think about what you can do to make life a little bit less unfair for the people who are not so fortunate. And I think that’s what we are trying to do. If we leave the world better than we found it, then that’s as good as it gets.

How do you approach philanthropy that might be different from another grant-making organization? Are there any ways that you want to be more entrepreneurial?

Gary: One of the things Mike Milken taught me is that there are two ways that you can do philanthropy. You can write a check to the art museum or the cancer foundation and say goodbye. And that’s fine if you don’t want to invest your time and so forth. But if you’re passionate about something—and that was his advice, find the things you’re passionate about—then you want to be deeply involved in the process so that you get the results that you want.

Alya: We try to be involved in areas where nobody else wants to go. Where it is not prestigious or popular. Where it is hard. We try to be innovative in philanthropy. We try to lead with the principles that Dr. Michelson applied to all his devices and discoveries: Be innovative. Don’t be afraid to disrupt things, and be creative.

What makes you proud about the work that is being done in the foundations?

Alya: In May, Financial Times published an article about how philanthropies devoted to medical research can make an impact. Dr. Michelson was featured, along with Bill Gates and others. The message about Dr. Michelson was, “This is how philanthropists can be catalytic with less funding but the same success.” I was proud of that. This is one core approach we have. Be catalytic and drive systemic change through philanthropy.

Gary: When we invest in high-quality, cutting-edge medical research, it’s with the idea that a single scientific breakthrough or discovery could affect the lives of hundreds of millions of people. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the largest funder of medical research in the world. They don’t fund young researchers, and they don’t fund high-risk, high-reward research. If you’re looking for disruptive breakthroughs, they go unfunded. Those are the things that we’ve been funding for 15 years.

Interestingly enough, 15 years ago, we began funding something called messenger interference, which has to do with how messenger RNA transcribes DNA. At the time, the NIH was not funding that at all. Five years later, they became the major funder of messenger interference. So far, our batting average has been pretty good because we seem to be ahead of the curve. We’ll continue to do that. We aim to contribute something that would not have happened but for us.

Alya: One last thing that we are very proud of is how many volunteers every single one of our foundations attracts. Whether it’s Michelson Found Animals, Michelson 20MM, or Michelson Medical Research Foundation, it’s unbelievable to see the people that bring so much to our programs and events. That’s a great thing and we give our thanks again to the people who work in the foundations with these volunteers. It’s wonderful.

Gary: I could not be more appreciative of our volunteers. It actually makes me smile. After the Adopt & Shop in Culver City opened, I used to run the steps over at Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook and I would stop by the Adopt & Shop on the way home. I’m pretty sure that nobody there knew who I was, and everyone had a smile on their faces—not just for me, but for everybody. They were all volunteers—they weren’t even being paid—but everyone had a great attitude. It felt good to walk in there.

“It is our responsibility to leave the world a better place than we found it—to make life a little less unfair for those less fortunate.” – DR. GARY K. MICHELSON

Do you have any hopes that you would like to impart for 2021?

Gary: At some point the COVID-19 crisis will pass, but I don’t think that will be the end to our need to reach out to try to make the world a little bit more fair—try to help where we can, help people to have the chance to live up to their potential. That is what’s going to continue to drive us.

Find out more about the diverse areas in which Michelson Philanthropies are engaged, and Alya and Dr. Michelson’s commitment to “make the world a little less unfair” in our 2021 Impact Report.